Lionel Messi

Reviving Art in Architecture: Looking at France’s ‘1% for Art’ Policy

© chris-johnson/Unsplash

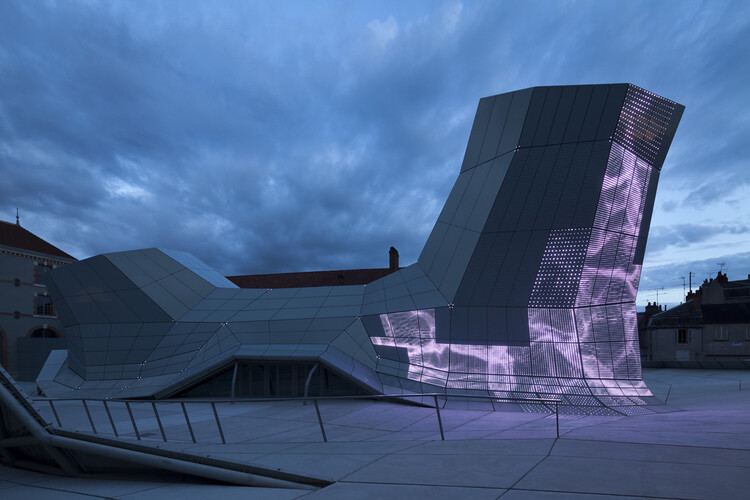

Throughout different historical cultures and artistic movements, from ancient Greece and Rome to the Renaissance and the Bauhaus, the interaction between art and architecture has been an important social statement. However, 20th century ideas of modernity and mass production resulted in the decline and disappearance of art in buildings.In response, many European countries have taken it upon themselves to promote collaboration between art and architecture. Plans were established that dictated that a percentage of the total cost of a new public building, site or area must be spent on the arts. This law, commonly known as ‘Percentage for Art’, originated in France and has been explored by artists and architects over the years to create new architectural experiences.+ 8Lavirotte Building, Facade is beautifully decorated with sculptures and ceramic tiles, Paris, France. Photo © Yana Fefelova/ShutterstockThe concept of this strategy was born in France in 1936, but it was not implemented until 1951. Initially, this strategy considered the role of art in architecture mainly as ‘decoration’, with the aim of strengthening school environment for students. However, this plan faced criticism due to its limitation in school buildings and the fact that the funds come only from the government. In response, the law was revised in 1972. It was expanded to include all public buildings, and the funds became a direct part of the project’s cost. This version meant that artists should participate in the creation of public architecture, increasing the popularity of the policy and the possibility of being the target of artists in society.Related ArticleReinventing Collaboration: Searching for Artistic Space with Mass-Produced Architecture Other countries soon adopted similar regulations. An Italian law of 1949 mandated that all public authorities provide 2% of their building costs for decoration. In Sweden, a policy that emerged in the 1930s required the government to provide half of 1% of the money for the arts, with architects responsible for the rest. The Netherlands enacted a law requiring that 1.5% of the cost of building new public buildings be allocated to the provision of interactive graphics. Similar laws were also established in Norway, Finland, the USA, and many other countries, to promote the integration of art in buildings.Azulejo tiles in Portugal. Image © Francesco Riccardo Iacomino/Getty ImagesOver the years, discussions about French policy have been unique. There were inevitable problems due to the excessive involvement of the architect in the production of the buildings, and the absence of the artist until the project was completed. This shows a basic ‘decoration’ suitable for an art fund. Separately, artists have strongly criticized the apparent lack of response to the project by regional and local authorities, as well as private developers. Other administrative issues include initial inflation, percentages, fees, and procedural delays.The debate about how contemporary art can be integrated with architecture has been prominent. The artists wanted to go beyond sculptures on facades, exploring all forms of art including sound, light, digital art, mixed media, and art. of the process. In 1983, in response to widespread opinion, the “percent for art” policy was applied to local governments through the decentralization act. In fact, one percent of the total amount of the public building budget in France, including taxes, must be allocated to drawings or design. This exchange provided opportunities for all professionals, to find the plan whose name is famous, “One Percent”.Georges-Freche School of Hotel Management. Image © Moreno Maggi; Georges-Freche School of Hotel Management / Massimiliano and Doriana FuksasThe Georges Frêches school in Montpellier is an important example of the use of this strategy. A total of €400,000 was awarded to the work of French designer Matali Crasset. He incorporated metal sculptures as lighting elements to enhance the interior environment of the building. Since 2004, six educational institutions have benefited from art installations, along with other public buildings in the country. The 1% strategy has become a highly respected commission among artists in the country, enabling them to explore the integration of their work with architecture and their interaction with society.EMULSION, GEORGES FRÊCHE LYCÉE, MONTPELLIER. Image © Jérôme SprietLes Turbulences FRAC Center by Jakob_MacFarlane artic intervention Electronic Shadows. Image © Nicolás BorelAnother example is “Les Turbulences at Orleans FRAC Center by Jakob + MacFarlane”, where the brief required an experimental design. The building was transitional, and was added to a 19th century building. Impressive structures made of steel rose from the ground, covered by Reynobond aluminum-composite panels. With the 1% strategy, the collaboration with the two artists of Electronic Shadow has allowed the integration of LEDs in Reynobond panels. This made large parts of the Riot a bright arena where images, patterns and messages could dance and unfold. The exterior of the building became a canvas to integrate digital art, creating a powerful urban statement.Les Turbulences FRAC Center by Jakob_MacFarlane artic intervention Electronic Shadows. Image © Nicolás BorelThese standards encourage the development of architecture by challenging architects to work within architectural challenges. According to Matali Crasset, in an interview with Ivo Bonacorsi about the commission of the Georges Frêches School, he said, “With the 1%, you know that you are in the same boat as the architects and their local offices. There is The specific needs of customers and the strict rules that must be followed. It’s not just arranging furniture or creating an art center. When I see the Fuksas building, you immediately realize that working outside would be and almost impossible I was asked to deal with the matter of inner light, and that is what I chose to deal with my relationship with the object of architecture simple creativity in the light.”EMULSION, GEORGES FRÊCHE LYCÉE, MONTPELLIER. Image © Jérôme SprietLes Turbulences FRAC Center by Jakob_MacFarlane artic intervention Electronic Shadows. Image © Nicolás BorelThe discussion about the role of art in creativity continues with initiatives like this, providing an example for other areas to follow. Art has always had the power to inspire and enhance the architectural experience, and these strategies ensure its continued existence. The French Ministry of Culture also recognizes the ongoing nature of this dialogue. In 2015, it introduced the “one building, one work” strategy, with the aim of bringing art closer to everyone, including private buildings. Their strategy not only supports artistic creation but also strives to promote visual arts to the widest possible audience, advocating the value of art within architectural experiences.

#Reviving #Art #Architecture #Frances #Art #Policy